There are numerous sources for the funerary rituals and spells Egyptians used to aid the dead over the threshold of the afterlife. They were written on papyrus and linen mummy wrappings, painted on coffins and carved on walls, texts now known collectively as the Book of the Dead. Mummification was an essential part of Egyptian funerary practice, the means by which the body would be able to rejoin the soul in the afterlife, but very little written material detailing the process has survived. Egyptologists believe this was deliberate, that the sacred art was transmitted orally from embalmer to embalmer.

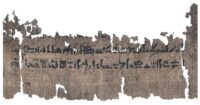

Only two papyri dedicated to mummification were previously known, but now a third has been found in an unexpected context: in the middle of a medical text on herbal treatments and swellings of the skin. Written back and front over 20 feet in length, it is second longest surviving Egyptian  medical papyrus. The Papyrus Louvre-Carlsberg (so named between it is in two parts, one in the collection of the Louvre Museum and the other University of Copenhagen’s Papyrus Carlsberg Collection) dates to around 1450 B.C., which makes it the oldest of the three mummification papyri by a thousand years. It is the earliest known Egyptian herbal treatise. The section on mummification covers details the other two never address.

medical papyrus. The Papyrus Louvre-Carlsberg (so named between it is in two parts, one in the collection of the Louvre Museum and the other University of Copenhagen’s Papyrus Carlsberg Collection) dates to around 1450 B.C., which makes it the oldest of the three mummification papyri by a thousand years. It is the earliest known Egyptian herbal treatise. The section on mummification covers details the other two never address.

University of Copenhagen Egyptologist Sofie Schiødt has translated and interpreted the papyrus for her doctoral dissertation.

“One of the exciting new pieces of information the text provides us with concerns the procedure for embalming the dead person’s face. We get a list of ingredients for a remedy consisting largely of plant-based aromatic substances and binders that are cooked into a liquid, with which the embalmers coat a piece of red linen. The red linen is then applied to the dead person’s face in order to encase it in a protective cocoon of fragrant and anti-bacterial matter. This process was repeated at four-day intervals.”

Although this procedure has not been identified before, Egyptologists have previously examined several mummies from the same period as this manual whose faces were covered in cloth and resin. […]

The importance of the Papyrus Louvre-Carlsberg manual in reconstructing the embalming process lies in its specification of the process being divided into intervals of four, with the embalmers actively working on the mummy every four days.

“A ritual procession of the mummy marked these days, celebrating the progress of restoring the deceased’s corporeal integrity, amounting to 17 processions over the course of the embalming period. In between the four-day intervals, the body was covered with cloth and overlaid with straw infused with aromatics to keep away insects and scavengers,” Sofie Schiødt says.

The papyrus is scheduled to be published in 2022.

The ancient Chinese approach (of which some utterly failed) was a different one. There are, however, exquisitely well preserved Chinese bodies in liquid, and I would be interested in the “processions” for the conservation of the tinned body, who was discovered after 600 years on the grounds of St Bees in 1981, obviously killed in Lithuania and sent back to Northern England: All intestines at their place and the body after 600 years in the ground perfectly flexible.

Notably, “Surströmming” –lightly-salted fermented Baltic Sea herring– is also tinned, but usually gasses are produced as fermentation is continued in the can (danger! don’t try this at home). Just enough salt is used to prevent the raw herring from rotting while still allowing it to ferment. Maybe, you just need to put more salt in the can.

Over a time period of way over 2000 years, their mummification processes slightly changed, as presumably did the “processions”. The mentioned 70 day (-2) period divided by four gives 17 “processions”. Half of the period was used for drying and the other half for wrapping. In the 5th century BC, Herodotus likewise reports of a 70 day period.

At any given time, I reckon, alternatives were offered, depending on how much the dead person’s family was willing and able to spend (cf. Herodotus Bk.2). I heard elsewhere that there was a method with pure natron, and another one with natron brine. A general principle seems to have been that the corpses were “dried”.

———–

“[Having removed the brain and all] they keep the body for embalming covered up in natron for seventy days, but for a longer time than this it is not permitted to embalm it; and when the seventy days are past, they wash the corpse and roll its whole body up in fine linen cut into bands, smearing these beneath with gum (κόμμι), which the Egyptians use generally instead of glue (κόλλα)./ ταῦτα δὲ ποιήσαντες ταριχεύουσι λίτρῳ κρύψαντες ἡμέρας ἑβδομήκοντα· πλεῦνας δὲ τουτέων οὐκ ἔξεστι ταριχεύειν. ἐπεὰν δὲ παρέλθωσι αἱ ἑβδομήκοντα, λούσαντες τὸν νεκρὸν κατειλίσσουσι πᾶν αὐτοῦ τὸ σῶμα σινδόνος βυσσίνης τελαμῶσι κατατετμημένοισι, ὑποχρίοντες τῷ κόμμι, τῷ δὴ ἀντὶ κόλλης τὰ πολλὰ χρέωνται Αἰγύπτιοι.”

———–