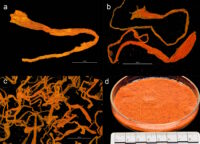

A new study of botanical materials found on the wreck of the Gribshunden, the 15th century Danish royal warship, has found it was laden with exotic spices, including the first archaeological evidence of saffron, ginger, cloves in medieval Scandinavia, previously only known from scant written sources instead of material remains. It is also the only known archaeological example of a complete royal spice larder from the Middle Ages. It is so well-preserved that the saffron still has its distinctive aroma after 527 years underwater.

A new study of botanical materials found on the wreck of the Gribshunden, the 15th century Danish royal warship, has found it was laden with exotic spices, including the first archaeological evidence of saffron, ginger, cloves in medieval Scandinavia, previously only known from scant written sources instead of material remains. It is also the only known archaeological example of a complete royal spice larder from the Middle Ages. It is so well-preserved that the saffron still has its distinctive aroma after 527 years underwater.

Gribshunden, the flagship of King Hans of Denmark and Norway, sank while anchored next to the island Stora Ekön off the Baltic coast of Ronneby, southern Sweden, in 1495. The king and his retinue had disembarked and were headed to a meeting with the regent of Sweden in Kalmar when the ship suddenly caught fire and quickly sank to the seabed 35 feet below the surface.

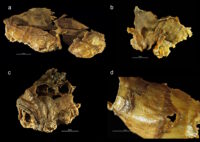

The wreck was first spotted in 1971 by local sports divers and it became a popular scuba site. Archaeologists only began to explore the site in 2001 after early iron gun carriages were found. Subsequent fieldwork revealed a carvel-built warship from the late 1400s that was unusually large for the period. It was also unusually well-armed and well-provisioned. Its design, contents and radiocarbon dating of the timbers identified it as the Gribshunden. It is the oldest armed warship found in Nordic waters.

The wreck was first spotted in 1971 by local sports divers and it became a popular scuba site. Archaeologists only began to explore the site in 2001 after early iron gun carriages were found. Subsequent fieldwork revealed a carvel-built warship from the late 1400s that was unusually large for the period. It was also unusually well-armed and well-provisioned. Its design, contents and radiocarbon dating of the timbers identified it as the Gribshunden. It is the oldest armed warship found in Nordic waters.

Built in 1485 in northern France or Belgium, Gribshunden was one of the first European naval vessels to be outfitted with guns and King Hans made ample of use it for a decade before its sinking. Its last trip in June 1495 was a diplomatic mission. Hans was attending a summit to convince the regent of Sweden and the Swedish Council to recreate the Kalmar Union by electing him King of Sweden. That would join the crown of Sweden to that of Denmark and Norway and reunite all of the Nordic countries under a single ruler.

Hans needed his flagship fully stocked with emblems of his hard power — shipboard artillery, a whole battalion of soldiers, armor, small arms — as well as his soft power — luxurious livery, books, enough food and drink for multiple royal courts to feast on — to impress the Swedish delegation. Archaeological evidence of this rich assemblage, even the organic elements, survived in exceptionally good condition thanks to the consistently low temperature and low salinity of Baltic waters. Thick algae deposits also create anaerobic zones that preserve archaeological remains from wooden crossbow stocks to fruit seeds.

Hans needed his flagship fully stocked with emblems of his hard power — shipboard artillery, a whole battalion of soldiers, armor, small arms — as well as his soft power — luxurious livery, books, enough food and drink for multiple royal courts to feast on — to impress the Swedish delegation. Archaeological evidence of this rich assemblage, even the organic elements, survived in exceptionally good condition thanks to the consistently low temperature and low salinity of Baltic waters. Thick algae deposits also create anaerobic zones that preserve archaeological remains from wooden crossbow stocks to fruit seeds.

In total, the study identified 3097 plant remains from 40 species. Spices dominate, representing 86% of the assemblage.

The plant material from Gribshunden contributes new knowledge about the foodstuffs consumed by the social elite in medieval Scandinavia. Considering that Gribshunden sank in the beginning of June, perishables such as ginger, grapes, berries, and cucumber were likely preserved as dried fruit, pickles, or jams to have been available for consumption all year around. It is unclear if ginger rhizomes were stored fresh or were preserved in some form. If fresh, the rhizomes must have been procured within days of Gribshunden’s departure from Copenhagen, as fresh ginger has a short shelf life. Other foodstuffs recovered from Gribshunden could be stored for far longer than fresh ginger. Spices from far distant origin, such as black pepper, saffron, and cloves would keep for long periods if they remained dry. Dill, black mustard, and caraway were likely sourced locally. Flaxseeds, almond, and hazelnut have long storage lives. It is probable that nuts were stored on board in their shells and cracked opened when ready for consumption, as broken shell parts were recovered from both nut species.

It is tempting to compare this wide variety of fresh produce to records of medieval maritime provisioning; but as the royal flagship, Gribshunden is a special case. Instead, the exotic foodstuffs from the king’s spice cabinet provide a window into the consumption patterns that likely followed in the elite landscapes of castles ashore. Despite the popularity of exotic spices among the medieval aristocracy, very few of these foods have survived archaeologically. The preservation of these plant foods on Gribshunden constitutes a discovery of great historical value. Spices and other exotic foods such as almonds were typically consumed only by society’s wealthiest. On Gribshunden these were not victuals for the working crew. Exotic food items are probably some of the most easily identifiable indicators of social context. King Hans was travelling on the ship together with his courtiers; these expensive exotic foods are linked to these passengers.

Danish archival sources from 1487 relate brief but telling details specific to King Hans’ expenses and activities aboard his flagship. While laid up awaiting favorable winds in 1487 en route to Gotland and at a stop on Bornholm island on the return, Hans gambled on card games. In those few weeks, his recorded losses totaled 42 marks, nearly the annual salary of one of the ship’s senior officers. He ate candy and nuts, and with his companions, drank wine and particularly beer. On that voyage the ship reprovisioned with fresh barrels of local beer, as well as embstøll, a hopped Prussian beer originally brewed in Einbeck, Germany. Other recorded purchases for Hans’ sea voyages are consistent. He bought more confectionaries for the apothecary, nuts, and saffron while voyaging to Års, Jylland, Denmark. The amount of saffron purchased was prodigious: the cost was 36 mark danske, equivalent to nine months of salary for a senior officer on Gribshunden, or 18 months of salary for a sailor. These documentary references combined with the remains of saffron, almonds, and hazelnut recovered from Gribshunden’s 1495 wrecking prove that the king regularly consumed these extravagant foods while at sea, and most probably while ashore. […]

Had Gribshunden safely arrived in Kalmar, from its decks Hans would have employed all manner of elite signaling to impress the Swedish Council. The consumption of exotic foods certainly was symbolic of prestige and social superiority within Hans’ realm. It also demonstrated that King Hans and medieval Denmark were culturally integrated with the rest of Europe, and the world beyond the continental borders.