The oldest known bead in the Western Hemisphere has been discovered at the La Prele Mammoth site in Wyoming. Radiocarbon dating results indicate the tubular bone bead is approximately 12,940 years old.

The oldest known bead in the Western Hemisphere has been discovered at the La Prele Mammoth site in Wyoming. Radiocarbon dating results indicate the tubular bone bead is approximately 12,940 years old.

There are very few Early Paleoindian beads known to survive, and most of them are not securely dated because they are made of minerals (caliche, hematite) rather than bone. The bone beads on the archaeological record were found in slightly more recent contexts than the La Prele example.

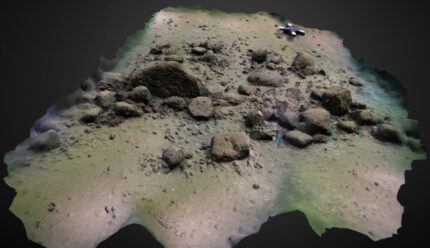

The La Prele Mammoth site was first excavated in 1987. They uncovered a Paleoindian camp where the remains of a young Columbian mammoth had been processed using chipped stone tools. Radiocarbon dates of the mammoth bones found the site was occupied around 12,940 years before the present. The bead was found in a hearth area of the site about 11 miles from the mammoth remains. Stone flake tools, bone needles and the butchered and burned remains of prehistoric bison were unearthed there, but the bead was not derived from bison bones.

Researchers employed zooarchaeology by mass spectrometry (ZooMS) to identify the animal the bone came from, and the material turned out to be lagomorph bone, most likely from a hare rather than a rabbit.

This finding represents the first secure evidence for the use of hares during the Clovis period, which refers to a prehistoric era in North America, particularly prominent about 12,000 years ago. It’s named after the Clovis archaeological site in New Mexico, where distinctive stone tools were discovered.

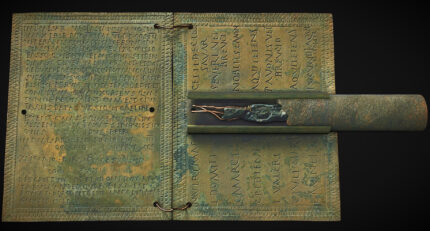

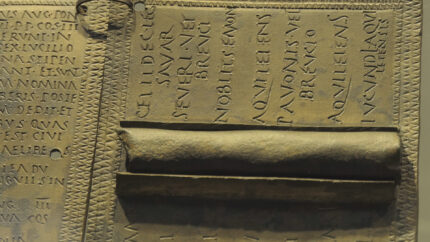

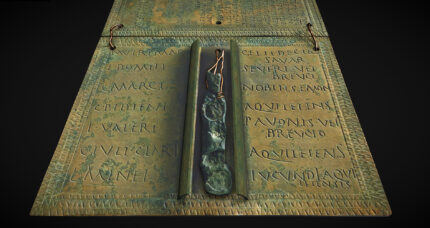

The bead is about 7 millimeters in length, and its internal diameter averages 1.6 millimeters. The research team considered the possibility that the bead could have been the result of carnivore consumption and digestion and not created by humans; however, carnivores were not common on this site, and the artifact was recovered 1 meter from a dense scatter of other cultural materials.

Additionally, the grooves on the outside of the bead are consistent with creation by humans, either with stones or their teeth. Beads like this one were likely used to decorate their bodies or clothing.

The findings have been published in the journal Scientific Reports and can be read in full here.