A hoard of Iron Age gold discovered in 1896 by farmers plowing a field in Broighter, near Limavady, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland, is coming home for a quick 11-day visit. The famed gold pieces, minus what is arguably the most famous piece of them all, will be on display at the Roe Valley Arts and Cultural Centre from November 12th through 23rd. This is the first homecoming for the artifacts which were sold away almost as quickly as they were found.

A hoard of Iron Age gold discovered in 1896 by farmers plowing a field in Broighter, near Limavady, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland, is coming home for a quick 11-day visit. The famed gold pieces, minus what is arguably the most famous piece of them all, will be on display at the Roe Valley Arts and Cultural Centre from November 12th through 23rd. This is the first homecoming for the artifacts which were sold away almost as quickly as they were found.

The Broighter Hoard dates to the 1st century B.C. and consists of a miniature boat made out of sheet gold, a sheet gold bowl, two torcs made of twisted gold bars, two loop-in-loop gold chains with terminal boxes of sheet gold, and a large hollow torc made of hammered sheet gold highly decorated with incised and high relief swirls and arcs. The boat is obsessively detailed, complete with oars, benches, a rudder, yardarm and various tools. It’s 7.25 inches long and three inches wide and extremely delicate. Its fragile condition is what prevented it from traveling to Limavady.

The workmanship suggests different places of origin for the pieces — southern England for the bar torcs, Roman Europe for the chains, Irish remodeling of a possibly English or German design for the tubular torc — but analysis of the metal content revealed traces of platinum characteristic of all Irish gold from the La Tène culture (a late Iron Age culture widespread in Europe north, east and west of the Alps). No native British or Irish gold has those traces of platinum; the raw material and/or artifacts made their way to Ireland via trade routes, possibly originating from the Rhine or perhaps from Lydia, today western Turkey.

The workmanship suggests different places of origin for the pieces — southern England for the bar torcs, Roman Europe for the chains, Irish remodeling of a possibly English or German design for the tubular torc — but analysis of the metal content revealed traces of platinum characteristic of all Irish gold from the La Tène culture (a late Iron Age culture widespread in Europe north, east and west of the Alps). No native British or Irish gold has those traces of platinum; the raw material and/or artifacts made their way to Ireland via trade routes, possibly originating from the Rhine or perhaps from Lydia, today western Turkey.

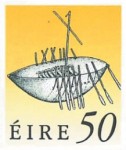

The boat and the tubular torc are the stars of the set, with the former having appeared on the Irish Millennium Pound minted in 2000 and both of them having appeared on their own stamps. These iconic emblems of Eire almost wound up in the British Museum. It took a lot of controversy and a court case to get them back on Irish soil, and even then they stayed down south in Dublin.

The boat and the tubular torc are the stars of the set, with the former having appeared on the Irish Millennium Pound minted in 2000 and both of them having appeared on their own stamps. These iconic emblems of Eire almost wound up in the British Museum. It took a lot of controversy and a court case to get them back on Irish soil, and even then they stayed down south in Dublin.

The saga begins in February of 1896 when two plowmen, Thomas Nicholl and James Morrow, working a double-plow arrangement where both men plow, one following the other to deepen the furrow which is relatively shallow on the first pass, turned up a muddy metal dish. Next to it in furrowed soil they found more metal pieces nested inside each other. They took the finds to the landowner, farmer Joseph L. Gibson, who had his maid wash them in the sink. She said in a later statement that “it is quite possible that some small objects may have been washed down the open drain, for it was not then known the finds were gold and no great care was taken in their cleaning.” :facepalm:

The saga begins in February of 1896 when two plowmen, Thomas Nicholl and James Morrow, working a double-plow arrangement where both men plow, one following the other to deepen the furrow which is relatively shallow on the first pass, turned up a muddy metal dish. Next to it in furrowed soil they found more metal pieces nested inside each other. They took the finds to the landowner, farmer Joseph L. Gibson, who had his maid wash them in the sink. She said in a later statement that “it is quite possible that some small objects may have been washed down the open drain, for it was not then known the finds were gold and no great care was taken in their cleaning.” :facepalm:

They didn’t look like much — the boat in particular had been damaged by the plow — but Gibson brought the hoard to a jeweler in Derry to see if they might be worth anything. The jeweler paid him £2 and then turned around sold them, doubtless for much more, to Cork antiquarian Robert Day. Robert Day had a Dublin goldsmith repair the pieces thus revealing the twisted lump to be a one of a kind boat model and sold the whole hoard to the British Museum for £600. These transactions were exposed to the public scrutiny in 1897 when British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans, famous for his discovery of the Palace of Knossos on Crete, wrote a paper about the artifacts.

They didn’t look like much — the boat in particular had been damaged by the plow — but Gibson brought the hoard to a jeweler in Derry to see if they might be worth anything. The jeweler paid him £2 and then turned around sold them, doubtless for much more, to Cork antiquarian Robert Day. Robert Day had a Dublin goldsmith repair the pieces thus revealing the twisted lump to be a one of a kind boat model and sold the whole hoard to the British Museum for £600. These transactions were exposed to the public scrutiny in 1897 when British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans, famous for his discovery of the Palace of Knossos on Crete, wrote a paper about the artifacts.

The Royal Irish Academy (RIA) responded with fury, insisting that these artifacts, bound by the ancient laws of treasure trove, belonged to the Crown, not to the British Museum and should be in Ireland. Treasure trove distinguishes between objects buried with the intent of later recovery and objects lost or discarded. It’s treasure and Crown property if whoever buried it meant to get it back; it’s not treasure and finders keepers if it was discarded. The British Museum claimed the hoard was deposited in Lough Foyle as a votive offering to the sea god Manannán Mac Lir and thus their purchase was legitimate.

The case went to court where it dragged on for years until in 1903 it reached the Royal Courts of Justice in London. Experts on both sides testified to whether the Broighter field was underwater when the hoard was deposited there. Thomas Nicholl hauled his cookies all the way to London to testify to his discovery of the objects. The judge couldn’t understand a word of his thick Derry accent, so they brought in an Oxford professor to translate for him. The fact they were found close together, some nested inside each other, was highly significant to the judge because it seemed impossible to him that someone could cast objects into the water and they could remain huddled together. Apparently it didn’t occur to anyone that they might have been wrapped up together in a bag or a box which had decayed into nothingness over the millennia.

The case went to court where it dragged on for years until in 1903 it reached the Royal Courts of Justice in London. Experts on both sides testified to whether the Broighter field was underwater when the hoard was deposited there. Thomas Nicholl hauled his cookies all the way to London to testify to his discovery of the objects. The judge couldn’t understand a word of his thick Derry accent, so they brought in an Oxford professor to translate for him. The fact they were found close together, some nested inside each other, was highly significant to the judge because it seemed impossible to him that someone could cast objects into the water and they could remain huddled together. Apparently it didn’t occur to anyone that they might have been wrapped up together in a bag or a box which had decayed into nothingness over the millennia.

Finally Justice Farwell ruled, a little peevishly, truth be told, in favor of the Crown/Royal Irish Academy. He didn’t buy the votive story at all. From his ruling:

“The court has been occupied for some considerable time in listening to fanciful suggestions more suited to the poem of a Celtic bard tan to the prose of a legal reporter. The defense has asked the court to infer the existence of an anthropomorphic deity; the existence of an unknown sea; and the existence of mythical Irish chiefs or kings who would be likely to make a surmised votive offering to this mythical Irish Neptune.”

I doubt the court was being asked to infer the existence of Manannán Mac Lir; just the belief in his existence leading to votives of precious objects. Still, the Judge was clearly over it and the British Museum was forced to turn over the Broighter Gold to the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin where it has remained ever since. Ironically, it is labeled now as a likely votive offering to the sea god. It seems that the RIA experts were wrong, and that the field actually was if not underwater at all times, a very soggy flood-prone marsh, in the first century B.C.

Anyway, after all this water under the bridge (so to speak) and all the drama of thrones and dominions, it’s nice to see the hoard get to visit home for a bit. It’s a pity it couldn’t have happened earlier. Thomas Nicholl died in 1964 at the age of 91 never having had the chance to see the treasure he co-discovered cleaned, restored and on display. His granddaughter Maureen says “it was one of Tom Nicholl’s great regrets in life that he never saw the Broighter Hoard displayed in the National Museum. Right up to his death in 1964 he was still keen to talk about that evening in February 1896, when he unearthed Ireland’s greatest collection of gold ornaments.”

Anyway, after all this water under the bridge (so to speak) and all the drama of thrones and dominions, it’s nice to see the hoard get to visit home for a bit. It’s a pity it couldn’t have happened earlier. Thomas Nicholl died in 1964 at the age of 91 never having had the chance to see the treasure he co-discovered cleaned, restored and on display. His granddaughter Maureen says “it was one of Tom Nicholl’s great regrets in life that he never saw the Broighter Hoard displayed in the National Museum. Right up to his death in 1964 he was still keen to talk about that evening in February 1896, when he unearthed Ireland’s greatest collection of gold ornaments.”

One of the most astonishing parts of this story is the fact that a translator was needed to make a Northern Irish farmer intelligible to English judges. Was the Ulster accent that incomprehensible a century ago?

It does seem extreme but on the other hand it’s a common enough phenomenon. I had some embarassing “can you repeat that please?” moments when I first encountered a deep southern accent, and US broadcasters think it happens often enough that they sometimes subtitle Scottish, Irish and various English accents.

Still, that judge gives me an overall feeling of snobbery, like that he found all this Irish stuff some quaint, quasi-pagan, superstitious nonsense. I doubt he put a lot of effort into understanding Mr. Nicholl.

True enough…watching films where people speak with working class Glaswegian accents, I really need subtitles (I’m Canadian)

Gie’t this doolally celeb glaswegian tramp character a pennye for’er cap a’ tea.